|

|

|

|

DAVID HALSTED

In

Search of the

Internet:

The Early

History of

Punched-card

Technology

from the

Jacquard loom

to IBM

The

Lounge at Iwan

Ries

Tuesday, February 2,

2016

5:30-8:30pm

Reservations

are required.

Where

did the internet

come from? One

story goes this

way:

In

the beginning,

electronic computers

were thought of as

giant calculators,

created in Cold War labs to help guide

artillery shells,

build bombs, and

detect incoming

bombers. The

Pentagon linked

descendants of these

machines into the

ARPANET, the network

that would become

the internet. By the

late 1980s the stage

was set for Tim

Berners-Lee’s

invention of the

World Wide Web, but

it was really with

the opening of the

Internet to

commercial traffic,

the appearance of

the Mosaic browser

in 1994, and the

Netscape IPO in 1995

that networked

computing exploded

into the culture as

a whole, setting the

stage for our own

world of ubiquitous

internet access and

algorithms, for

tablets, smart

phones, wearables,

and the Internet of

Things. In a

nutshell, that is

the story of

computing and the

internet as it is

often told.

labs to help guide

artillery shells,

build bombs, and

detect incoming

bombers. The

Pentagon linked

descendants of these

machines into the

ARPANET, the network

that would become

the internet. By the

late 1980s the stage

was set for Tim

Berners-Lee’s

invention of the

World Wide Web, but

it was really with

the opening of the

Internet to

commercial traffic,

the appearance of

the Mosaic browser

in 1994, and the

Netscape IPO in 1995

that networked

computing exploded

into the culture as

a whole, setting the

stage for our own

world of ubiquitous

internet access and

algorithms, for

tablets, smart

phones, wearables,

and the Internet of

Things. In a

nutshell, that is

the story of

computing and the

internet as it is

often told.

But

this version of

the story

makes it hard to

understand how the

giant defense

calculators evolved

into social

machines—into

devices we use to

communicate and

interact. That

part of computing

history makes more

sense when we start

the story a little

earlier. In

the textile mills of

the Industrial

Revolution, Jacquard

looms used loops of

punched cards to

stored complex

patterns for woven

cloth.

Charles Babbage

dreamed of using

similar cards to

program his

never-built

Analytical Engine,

and his intellectual

partner, Ada,

Countess of

Lovelace, the

daughter of Lord

Byron, saw that the

Engine could handle

not just numbers,

but symbols of any

sort. But

this version of

the story

makes it hard to

understand how the

giant defense

calculators evolved

into social

machines—into

devices we use to

communicate and

interact. That

part of computing

history makes more

sense when we start

the story a little

earlier. In

the textile mills of

the Industrial

Revolution, Jacquard

looms used loops of

punched cards to

stored complex

patterns for woven

cloth.

Charles Babbage

dreamed of using

similar cards to

program his

never-built

Analytical Engine,

and his intellectual

partner, Ada,

Countess of

Lovelace, the

daughter of Lord

Byron, saw that the

Engine could handle

not just numbers,

but symbols of any

sort.

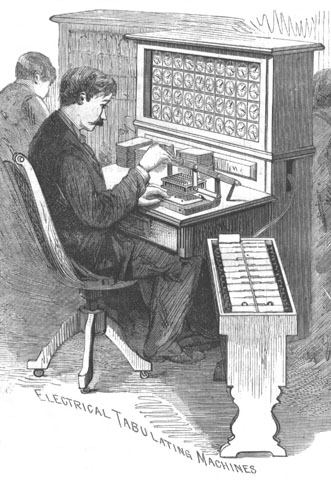

At the end of the

19th century the

American-born son of

a German immigrant,

Herman Hollerith,

implemented a system

that used punched

cards to handle

data.

Working in tandem

with John Shaw

Billings, a

physician and

statistician (and

the first director

of the New York

Public Library),

Hollerith’s punched

cards and tabulators

helped process the

1890 US census in

record time. Then he

turned to other

kinds of data, for

railroads, insurance

and the retail

trade. One of

the first

large-scale retail

installations, at

Marshall Field and

Company, was

churning through

10,000 cards a day

by 1907.  The

company Hollerith

founded would become

IBM; punched cards

would become the

mainstay of

information storage

and processing until

the digital

electronic computer

displaced them. The

company Hollerith

founded would become

IBM; punched cards

would become the

mainstay of

information storage

and processing until

the digital

electronic computer

displaced them.

Hollerith’s

expansion into

different markets

was based on the

idea that

information

technology could be

used to represent,

recombine and

manipulate many

kinds of objects in

the

world.

The modern computer

is much more than a

calculator because

it participates in

and helps us build

our culture.

It can do this

because of the

representational

flexibility that

traces back to the

punched card.

When we watch Herman

Hollerith stretch

the limits of the

technology he

invented, we see our

own world in the

making.

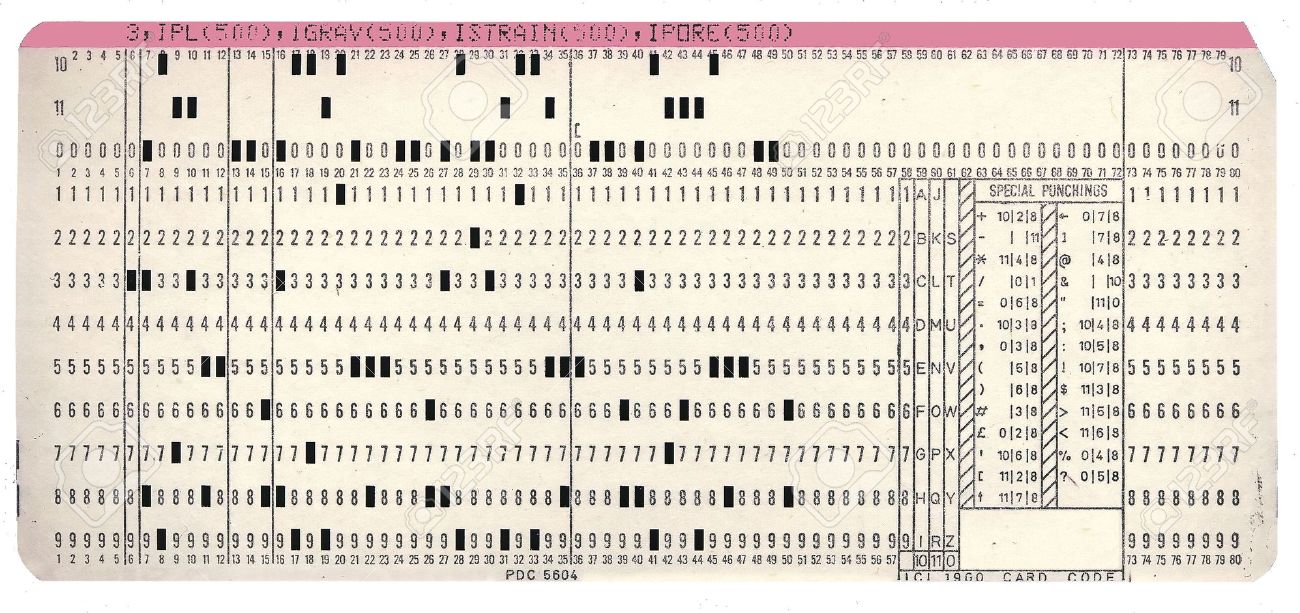

In the textile mills

of the Industrial

Revolution, Jacquard

looms used loops of

punched cards to

stored complex

patterns for woven

cloth. By the

end of the 19th

century, punched

card technology was

being used to

process census,

health, and business

data.  The

leading company in

punched card

technology, IBM,

would play a key

role in history of

electronic

computing.

This presentation

describes how the

punched card evolved

and how it

contributed to the

information

revolution as we

know it today. The

leading company in

punched card

technology, IBM,

would play a key

role in history of

electronic

computing.

This presentation

describes how the

punched card evolved

and how it

contributed to the

information

revolution as we

know it today.

David

Halsted has a

BA (St. John’s,

Annapolis, 1983) and

a PhD in comparative

literature

(University of

Michigan,

1991). David

Halsted has a

BA (St. John’s,

Annapolis, 1983) and

a PhD in comparative

literature

(University of

Michigan,

1991).

Dr.

Halsted writes,

"I

have a

background as

both an academic

and a

technologist.

I’ve taught

college-level

courses in

literature and

history and have

been working on

web

pages and

applications

since the

mid-1990s.

I recently left

the University

of Illinois at

Chicago, where I

was Director of

Online and

Blended Learning

in the College

of Liberal Arts

and Sciences, to

pursue freelance

and start-up

projects."

|

|

About

the

Cigar Society of

Chicago

ONE OF

THE OLDEST AND greatest

traditions of the city

clubs of Chicago is the

discussion of

intellectual, social,

legal, artistic,

historical, scientific,

musical, theatrical, and

philosophical issues in

the company of educated,

bright, and

appropriately

provocative individuals,

all under the beneficent

influence of substantial

amounts of tobacco and

spirits. The

Cigar Society of

Chicago

embraces this tradition

and extends it with its

Informal Smokers,

University Series

lectures, and Cigar

Society Dinners,

in which cigars, and

from time to time pipes

and cigarettes, appear

as an important

component of our version

of the classical

symposium. To be

included in the Cigar

Society's mailing list,

write to the secretary

at

curtis.tuckey@logicophilosophicus.org

|

|

|

|

|